altitude

Altitude is the angle between the horizon (a horizontal plane) and the sun’s position in the sky, measured in degrees.

Altitude or height (sometimes known as depth) is defined based on the context in which it is used (aviation, geometry, geographical survey, sport, and many more). As a general definition, altitude is a distance measurement, usually in the vertical or “up” direction, between a reference datum and a point or object. The reference datum also often varies according to the context. Although the term altitude is commonly used to mean the height above sea level of a location, in geography the term elevation is often preferred for this usage.

Vertical distance measurements in the “down” direction are commonly referred to as depth.

In aviation[edit]

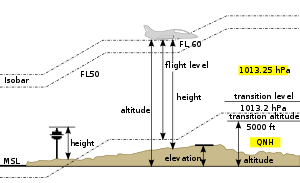

In aviation, the term altitude can have several meanings, and is always qualified by either explicitly adding a modifier (e.g. “true altitude”), or implicitly through the context of the communication. Parties exchanging altitude information must be clear which definition is being used.[1]

Aviation altitude is measured using either mean sea level (MSL) or local ground level (above ground level, or AGL) as the reference datum.

Pressure altitude divided by 100 feet (30 m) as the flight level, and is used above the transition altitude (18,000 feet (5,500 m) in the US, but may be as low as 3,000 feet (910 m) in other jurisdictions); so when the altimeter reads 18,000 ft on the standard pressure setting the aircraft is said to be at “Flight level 180”. When flying at a flight level, the altimeter is always set to standard pressure (29.92 inHg or 1013.25 hPa).

On the flight deck, the definitive instrument for measuring altitude is the pressure altimeter, which is an aneroid barometer with a front face indicating distance (feet or metres) instead of atmospheric pressure.

There are several types of aviation altitude:

- Indicated altitude is the reading on the altimeter when it is set to the local barometric pressure at mean sea level. In UK aviation radiotelephony usage, the vertical distance of a level, a point or an object considered as a point, measured from mean sea level; this is referred to over the radio as altitude.(see QNH)[2]

- Absolute altitude is the height of the aircraft above the terrain over which it is flying. It can be measured using a radar altimeter (or “absolute altimeter”).[1] Also referred to as “radar height” or feet/metresabove ground level (AGL).

- True altitude is the actual elevation above mean sea level. It is indicated altitude corrected for non-standard temperature and pressure.

- Height is the elevation above a ground reference point, commonly the terrain elevation. In UK aviation radiotelephony usage, the vertical distance of a level, a point or an object considered as a point, measured from a specified datum; this is referred to over the radio as height, where the specified datum is the airfield elevation (see QFE)[2]

- Pressure altitude is the elevation above a standard datum air-pressure plane (typically, 1013.25 millibars or 29.92″ Hg). Pressure altitude is used to indicate “flight level” which is the standard for altitude reporting in the U.S. in Class A airspace (above roughly 18,000 feet). Pressure altitude and indicated altitude are the same when the altimeter setting is 29.92″ Hg or 1013.25 millibars.

- Density altitude is the altitude corrected for non-ISA International Standard Atmosphere atmospheric conditions. Aircraft performance depends on density altitude, which is affected by barometric pressure, humidity and temperature. On a very hot day, density altitude at an airport (especially one at a high elevation) may be so high as to preclude takeoff, particularly for helicopters or a heavily loaded aircraft.

These types of altitude can be explained more simply as various ways of measuring the altitude:

- Indicated altitude – the altitude shown on the altimeter.

- Absolute altitude – altitude in terms of the distance above the ground directly below

- True altitude – altitude in terms of elevation above sea level

- Height – altitude in terms of the distance above a certain point

- Pressure altitude – the air pressure in terms of altitude in the International Standard Atmosphere

- Density altitude – the density of the air in terms of altitude in the International Standard Atmosphere

In atmospheric studies[edit]

Atmospheric regions[edit]

The Earth’s atmosphere is divided into several altitude regions. These regions start and finish at varying heights depending on season and distance from the poles. The altitudes stated below are averages:[3]

- Troposphere — surface to 8,000 metres (5.0 mi) at the poles – 18,000 metres (11 mi) at the equator, ending at the Tropopause.

- Stratosphere — Troposphere to 50 kilometres (31 mi)

- Mesosphere — Stratosphere to 85 kilometres (53 mi)

- Thermosphere — Mesosphere to 675 kilometres (419 mi)

- Exosphere — Thermosphere to 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi)

High altitude and low pressure[edit]

Regions on the Earth‘s surface (or in its atmosphere) that are high above mean sea level are referred to as high altitude. High altitude is sometimes defined to begin at 2,400 metres (8,000 ft) above sea level.[4][5][6]

At high altitude, atmospheric pressure is lower than that at sea level. This is due to two competing physical effects: gravity, which causes the air to be as close as possible to the ground; and the heat content of the air, which causes the molecules to bounce off each other and expand.[7]

High altitude and low temperature[edit]

The temperature profile of the atmosphere is a result of an interaction between radiation and convection. Sunlight in the visible spectrum hits the ground and heats it. The ground then heats the air at the surface. If radiation were the only way to transfer heat from the ground to space, the greenhouse effect of gases in the atmosphere would keep the ground at roughly 333 K (60 °C; 140 °F), and the temperature would decay exponentially with height.[8]

However, when air is hot, it tends to expand, which lowers its density. Thus, hot air tends to rise and transfer heat upward. This is the process of convection. Convection comes to equilibrium when a parcel at air at a given altitude has the same density as its surroundings. Air is a poor conductor of heat, so a parcel of air will rise and fall without exchanging heat. This is known as an adiabatic process, which has a characteristic pressure-temperature curve. As the pressure gets lower, the temperature decreases. The rate of decrease of temperature with elevation is known as the adiabatic lapse rate, which is approximately 9.8 °C per kilometer (or 5.4 °F per 1000 feet) of altitude.[8]

Note that the presence of water in the atmosphere complicates the process of convection. Water vapor contains latent heat of vaporization. As air rises and cools, it eventually becomes saturated and cannot hold its quantity of water vapor. The water vapor condenses (forming clouds), and releases heat, which changes the lapse rate from the dry adiabatic lapse rate to the moist adiabatic lapse rate (5.5 °C per kilometer or 3 °F per 1000 feet[9] As an average, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) defines an international standard atmosphere (ISA) with a temperature lapse rate of 6.49 °C per kilometer (3.56 °F per 1,000 feet).[10] The actual lapse rate can vary by altitude and by location.

Finally, note that only the troposphere (up to approximately 11 kilometres (36,000 ft) of altitude) in the Earth’s atmosphere undergoes convection: the stratosphere does not have convection.[11]

Effects on organisms[edit]

Humans[edit]

Medicine recognizes that altitudes above 1,500 metres (4,900 ft) start to affect humans,[12] and there is no record of humans living at extreme altitudes above 5,500–6,000 metres (18,000–19,700 ft) for more than two years.[13] As the altitude increases, atmospheric pressure decreases, which affects humans by reducing the partial pressure of oxygen.[14] The lack of oxygen above 2,400 metres (8,000 ft) can cause serious illnesses such as altitude sickness, high altitude pulmonary edema, and high altitude cerebral edema.[6]The higher the altitude, the more likely are serious effects.[6] The human body can adapt to high altitude by breathing faster, having a higher heart rate, and adjusting its blood chemistry.[15][16] It can take days or weeks to adapt to high altitude. However, above 8,000 metres (26,000 ft), (in the “death zone“), altitude acclimatization becomes impossible.[17]

There is a significantly lower overall mortality rate for permanent residents at higher altitudes.[18] Additionally, there is a dose response relationship between increasing elevation and decreasing obesity prevalence in the United States.[19] In addition, the recent hypothesis suggests that high altitude could be protective against Alzheimer’s disease via action of erythropoietin, a hormone released by kidney in response to hypoxia.[20] However, people living at higher elevations have a statistically significant higher rate of suicide.[21] The cause for the increased suicide risk is unknown so far.[21]

Athletes[edit]

For athletes, high altitude produces two contradictory effects on performance. For explosive events (sprints up to 400 metres, long jump, triple jump) the reduction in atmospheric pressure signifies less atmospheric resistance, which generally results in improved athletic performance.[22] For endurance events (races of 5,000 metres or more) the predominant effect is the reduction in oxygen which generally reduces the athlete’s performance at high altitude. Sports organizations acknowledge the effects of altitude on performance: the International Association of Athletic Federations (IAAF), for example, marks record performances achieved at an altitude greater than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) with the letter “A”.[23]

Athletes also can take advantage of altitude acclimatization to increase their performance. The same changes that help the body cope with high altitude increase performance back at sea level.[24][25] These changes are the basis of altitude training which forms an integral part of the training of athletes in a number of endurance sports including track and field, distance running, triathlon, cycling and swimming.

Other organisms[edit]

Decreased oxygen availability and decreased temperature make life at high altitude challenging. Despite these environmental conditions, many species have been successfully adapted at high altitudes. Animals have developed physiological adaptations to enhance oxygen uptake and delivery to tissues which can be used to sustain metabolism. The strategies used by animals to adapt to high altitude depend on their morphology and phylogeny. For example, small mammals face the challenge of maintaining body heat in cold temperatures, due to their small volume to surface area ratio. As oxygen is used as a source of metabolic heat production, the hypobaric hypoxia at high altitudes is problematic.

There is also a general trend of smaller body sizes and lower species richness at high altitudes, likely due to lower oxygen partial pressures.[26] These factors may decrease productivity in high altitude habitats, meaning there will be less energy available for consumption, growth, and activity.[27]

However, some species, such as birds,thrive at high altitude.[28] Birds thrive because of physiological features that are advantageous for high-altitude flight.

See also[edit]

- Atmosphere of Earth

- List of capital cities by altitude

- Coffin corner (aerodynamics) At higher altitudes, the air density is lower than at sea level. At a certain altitude it is very difficult to keep the airplane in stable flight.

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Air Navigation. Department of the Air Force. 1 December 1989. AFM 51-40.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Radiotelephony Manual. UK Civil Aviation Authority. 1 January 1995. ISBN 0-86039-601-0. CAP413.

- Jump up^ “Layers of the Atmosphere”. JetStream, the National Weather Service Online Weather School. National Weather Service. Archived from the original on 19 December 2005. Retrieved 22 December 2005.

- Jump up^ Webster’s New World Medical Dictionary. Wiley. 2008. ISBN 978-0-470-18928-3.

- Jump up^ “An Altitude Tutorial”. International Society for Mountain Medicine. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Cymerman, A; Rock, PB (1994). “Medical Problems in High Mountain Environments. A Handbook for Medical Officers”. USARIEM-TN94-2. U.S. Army Research Inst. of Environmental Medicine Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division Technical Report. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- Jump up^ “Atmospheric pressure”. NOVA Online Everest. Public Broadcasting Service.Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2009.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Goody, Richard M.; Walker, James C.G. (1972). “Atmospheric Temperatures”(PDF). Atmospheres. Prentice-Hall.

- Jump up^ “Dry Adibatic Lapse Rate”. tpub.com. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- Jump up^ Manual of the ICAO Standard Atmosphere (extended to 80 kilometres (262 500 feet))(Third ed.). International Civil Aviation Organization. 1993. ISBN 92-9194-004-6. Doc 7488-CD.

- Jump up^ “The stratosphere: overview”. UCAR. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- Jump up^ “Non-Physician Altitude Tutorial”. International Society for Mountain Medicine.Archived from the original on 23 December 2005. Retrieved 22 December 2005.

- Jump up^ West, JB (2002). “Highest permanent human habitation”. High Altitude Medical Biology3 (4): 401–407. doi:10.1089/15270290260512882. PMID 12631426.

- Jump up^ Peacock, Andrew J (17 October 1998). “Oxygen at high altitude”. British Medical Journal 317 (7165): 1063–1066. doi:10.1136/bmj.317.7165.1063. PMC 1114067.PMID 9774298.

- Jump up^ Young, Andrew J.; Reeves, John T. (2002). “21”. Human Adaptation to High Terrestrial Altitude. In: Medical Aspects of Harsh Environments 2. Borden Institute, Washington, DC. Archived from the original on 11 January 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- Jump up^ Muza, SR; Fulco, CS; Cymerman, A (2004). “Altitude Acclimatization Guide”. U.S. Army Research Inst. of Environmental Medicine Thermal and Mountain Medicine Division Technical Report (USARIEM–TN–04–05). Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- Jump up^ “Everest:The Death Zone”. Nova. PBS. 1998-02-24.

- Jump up^ West, John B. (January 2011). “Exciting Times in the Study of Permanent Residents of High Altitude”. High Altitude Medicine & Biology 12 (1): 1.doi:10.1089/ham.2011.12101.

- Jump up^ Voss, JD; Masuoka, P; Webber, BJ; Scher, AI; Atkinson, RL (2013). “Association of Elevation, Urbanization and Ambient Temperature with Obesity Prevalence in the United States”. International Journal of Obesity 37 (10): 1407–1412. doi:10.1038/ijo.2013.5.PMID 23357956.

- Jump up^ Ismailov, RM (Jul–Sep 2013). “Erythropoietin and epidemiology of Alzheimer disease”.Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 27 (3): 204–6. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e31827b61b8.PMID 23314061.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Brenner, Barry; Cheng, David; Clark, Sunday; Camargo, Carlos A., Jr (Spring 2011).”Positive Association between Altitude and Suicide in 2584 U.S. Counties”. High Altitude Medicine & Biology 12 (1): 31–5. doi:10.1089/ham.2010.1058.PMC 3114154. PMID 21214344.

- Jump up^ Ward-Smith, AJ (1983). “The influence of aerodynamic and biomechanical factors on long jump performance”. Journal of Biomechanics 16 (8): 655–658. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(83)90116-1. PMID 6643537.

- Jump up^ “IAAF World Indoor Lists 2012”. IAAF Statistics Office. 2012-03-09. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-22.

- Jump up^ Wehrlin, JP; Zuest, P; Hallén, J; Marti, B (June 2006). “Live high—train low for 24 days increases hemoglobin mass and red cell volume in elite endurance athletes”. J. Appl. Physiol. 100 (6): 1938–45. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01284.2005. PMID 16497842. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- Jump up^ Gore, CJ; Clark, SA; Saunders, PU (September 2007). “Nonhematological mechanisms of improved sea-level performance after hypoxic exposure”. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39(9): 1600–9. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3180de49d3. PMID 17805094. Retrieved2009-03-05.

- Jump up^ Jacobsen, Dean (24 September 2007). “Low oxygen pressure as a driving factor for the altitudinal decline in taxon richness of stream macroinvertebrates”. Oecologia 154 (4): 795–807. doi:10.1007/s00442-007-0877-x. PMID 17960424.

- Jump up^ Rasmussen, Joseph B.; Robinson, Michael D.; Hontela, Alice; Heath, Daniel D. (8 July 2011). “Metabolic traits of westslope cutthroat trout, introduced rainbow trout and their hybrids in an ecotonal hybrid zone along an elevation gradient”. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 105: 56–72. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2011.01768.x.

- Jump up^ McCracken, K. G.; Barger, CP; Bulgarella, M; Johnson, KP; et al. (October 2009). “Parallel evolution in the major haemoglobin genes of eight species of Andean waterfowl”.Molecular Evolution 18 (19): 3992–4005. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04352.x.PMID 19754505.